Gzip Is Cracked

A summary of an experiment to see the literal bytes compressed by Gzip

I’ve always considered myself a compression skeptic. Call me ignorant, but I never truly understood the impact that compression can have. Likely a product of growing up in a cloud native generation, but I never had to think about compression in a serious way, so I think I’ve always taken it for granted.

This changed recently, I got the chance to work with the Hatchet team to help them implement Gzip compression on both their engine (server) and client (SDK’s go, typescript, python). In this post I hope to go through the actual data of how compression can help, the trade offs and my (very limited) experience implementing Gzip compression for a GRPC server.

Why Compress

I can’t speak to all cases, but the primary modification in our case was to reduce network IO. The goal here was to reduce the number of bytes transmitted over the wire. This was really an effort to reduce costs as less bytes moving in and our of the the network results in less costs.

There are other reasons you might want to compress your data such as moving large amounts of data faster if Network IO is your bottleneck. This does have tradeoffs that we ran into that I’ll dive in deeper towards the end of the post.

What is Gzip Compression?

Gzip compression is likely one of the few compressions you’ve have seen while debugging. If you’ve ever inspected a HTTP request, it can be found under the Content-Encoding header. At a high level the idea is to a) deflate redundant data, essentially don’t repeat yourself. Then with that simplified data, b) extract frequent words and represent them with smaller sized bytes.

Full disclosure: I'm by no means a compression expert, this is my very rudimentary understanding of how Gzip compression works. If you want a deeper dive, I recommend taking a look at this article

There are two parts to this, lets go through an example by compressing the string:

> the cat in the hat

Step 1: Sliding Window Compression (LZ77)

Intuitively you can see in that string, the string the is repeated twice. So in a perfect world we don't have to save the twice. And thats the gist of the first step here, we loop over the string, and over our look-back sliding window (defaulting to 32KB) we can start our compression:

> the cat in the hat

> ^^^

Now that we've found a repeated pattern, time to reference the original pattern,

> the cat in (length=3,offset=11) hat

This is now saying, when we get to (length=3,offset=11), go back 10 bytes (to the start of the string), and copy 3 bytes (e.g. the that appears at the start).

Step 2: Huffman Coding

Now that you’ve found all repeated patterns, if you used this directly, you wouldn’t save a terrible amount of space. Its still better than repeating yourself, but we can do even better.

This is where entropy compression comes in. Think of texting jargon as an analogy. We do this on a daily basis; saying “laughing out loud” takes up too much time, we’ve simplified it to “lol”. Saying “okay” similarly is a common phrase, we’ve shortened it to “k” since we use it all the time.

Huffman Coding does something similar, but with generic data. It allows us to takes bytes that might appear very often, and represent them with smaller bytes. Back to our example, we have 4 spaces that appear in our string

> the cat in the hat

> ^ ^ ^ ^

The literal space character in ASCII is represented by the decimal 32, which converted to binary is 00100000. But we don't need to take up all that space (no pun intended) every time, since we know its very common, why couldn't we just represent it as a 01? As long as we're consistent, there are no rules against this. We could do something similar with the letter t, it appears 4 times, in binary it would be 01110100, but why couldn't we represent it as 00? Expanding this

| Symbol | Frequency | Huffman code |

| ------ | --------: | :----------: |

| `t` | 3 | `00` |

| ` ` | 4 | `01` |

| `h` | 3 | `110` |

| `a` | 2 | `100` |

| `c` | 1 | `1010` |

| `i` | 1 | `1011` |

| `n` | 1 | `1110` |

| `e` | 2 | `1111` |

We’ve simplified this string significantly by understanding in the context of this data whats the more popular items being sent, and then replacing them with short hand notation. Similar to how we use k to communicate the word okay. (To over communicate, in reality this is sent as a binary tree over the wire).

And that’s it! We can send these two items over the wire now and we’ve compressed the original message! The other end can take the Huffman encoding we’ve done, along with the compressed string and decoded to get the original string.

Setting Up The Experiment

I truly wanted to captures bytes when testing this, avoiding anything like log statements or scripts to ‘demonstrate compression’. To do this I setup isolated containers and then setup a script to monitor the literal bytes going in and our of the container.

Note: To give a bit of context here, Hatchet is a distributed queue platform, think Rabbit, SQS etc. This means that their primary payload is unstructured JSON. Hatchet uses a server that exposes a gRPC connection that was built in Golang.

After building a container for each SDK (Python, Typescript and Golang), in each I setup a test to send 10 identical messages over the wire. This way I could compare what its like to send these messages before and after I enable compression.

To measure the network, I used dockers built in stats function to extract NetIO:

docker stats —no-stream —format “{{.NetIO}}”

You can read more about this command here, but quoting the docs this field:

The amount of data the container has received and sent over its network interface

I would capture the network IO every 5 seconds, write that to a file, and then use that to calculate the final ‘bytes transferred over the wire’ that is used in the final calculation. Here is a snipper from one of my go tests:

Initial: 7.63kB / 4.53kB

8.04kB / 5.02kB

30.6kB / 21.2kB

Final: 31.3kB / 22.1kB

I engage folks to check out the source code as its all open source code.

Results

As expected Gzip compression transferred less bytes over the wire compared to no compression, but I was not expecting the sheer amount of data that was able to be compressed.

Pre-compression:

Starting with the pre-compression results:

Python

=== Test Results ===

SDK: python

State: disabled

RX Bytes: 1.04 MB (1090519 bytes)

TX Bytes: 30.72 KB (31457 bytes)

Total Bytes: 1.07 MB (1121976 bytes)

Typescript

=== Test Results ===

SDK: typescript

State: disabled

RX Bytes: 2.08 MB (2179840 bytes)

TX Bytes: 1.06 MB (1111364 bytes)

Total Bytes: 3.14 MB (3291204 bytes)

Golang

=== Test Results ===

SDK: go

State: disabled

RX Bytes: 2.10 MB (2199163 bytes)

TX Bytes: 1.06 MB (1109166 bytes)

Total Bytes: 3.16 MB (3308329 bytes)

This can be thought of as the baseline, this is what no compression gets you if you just send data over the wire.

Post-compression:

After enabling compression on both the server side and the client side these were the results:

Python

=== Test Results ===

SDK: python

State: enabled

RX Bytes: 19.80 KB (20275 bytes)

TX Bytes: 28.80 KB (29491 bytes)

Total Bytes: 48.60 KB (49766 bytes)

Typescript

=== Test Results ===

SDK: typescript

State: enabled

RX Bytes: 3.54 KB (3625 bytes)

TX Bytes: 7.44 KB (7615 bytes)

Total Bytes: 10.98 KB (11240 bytes)

Golang

=== Test Results ===

SDK: go

State: enabled

RX Bytes: 19.85 KB (20327 bytes)

TX Bytes: 15.84 KB (16220 bytes)

Total Bytes: 35.69 KB (36547 bytes)

To explicitly compare them:

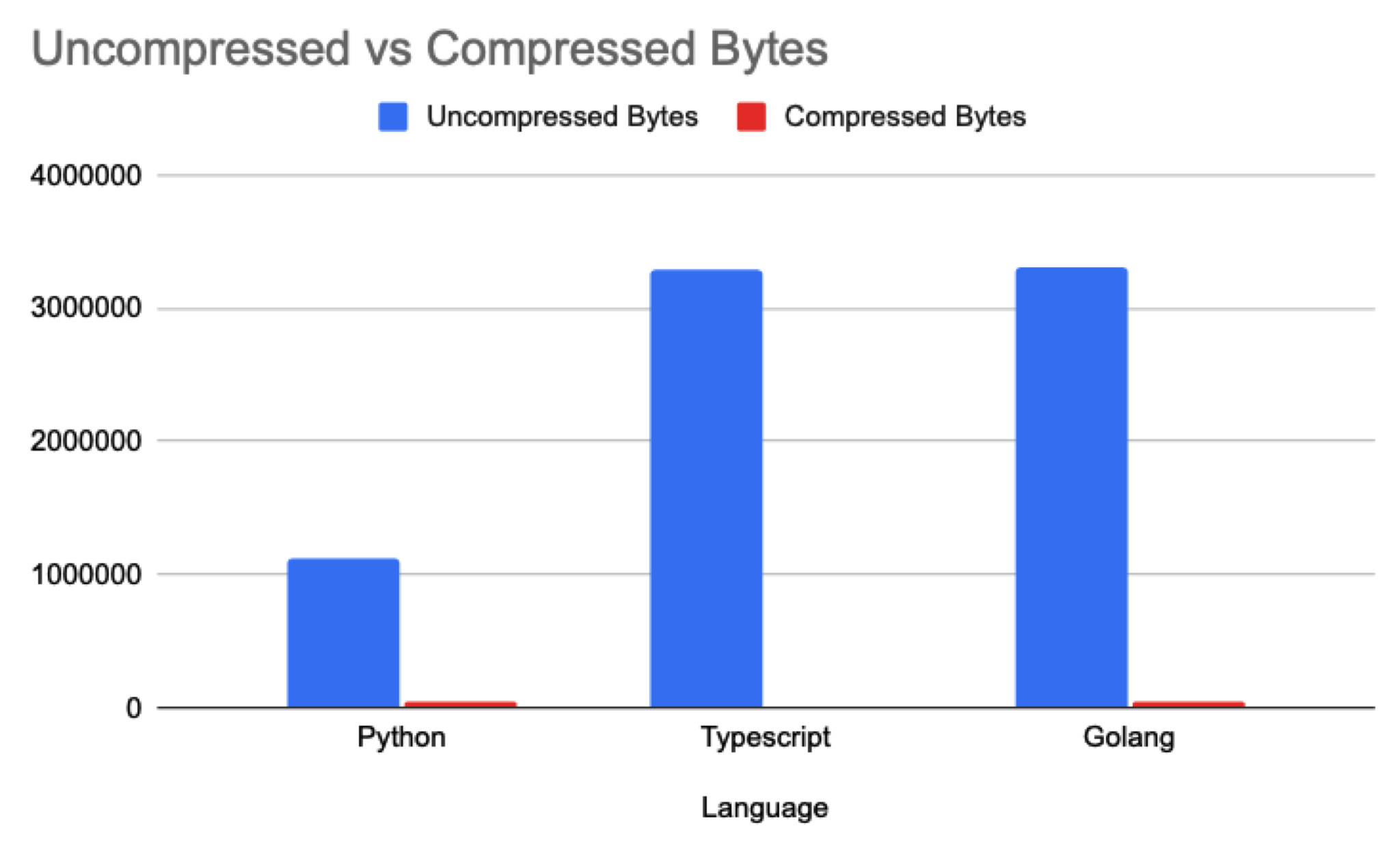

Python: 1.07mb -> 48.6kb (95.46% smaller)

Typescript: 3.14mb -> 10.98kb (99.65% smaller)

Golang: 3.16mb -> 35.69kb (98.87% smaller)

Graphing this data is quite humorous as you can barely see the compressed bytes compared to the uncompressed version:

So whats the catch?

Gzip compression is cracked, we were able to get 99%+ smaller data transferred over the wire in typescript and generally 95%+ smaller across the all 3 SDKs. I was expecting smaller payloads, but to be able to compress 99% of the data was very surprising to me.

This seems amazing right? Why wouldn’t we always do this? Well there is one gotcha with this: Gzip compression is making a tradeoff between CPU vs Network IO. We saw this directly with one of the integration tests we had setup on the pull request.

One of the tests acts as a regression test to ensure that any changes does not make things slower, to do this it similarly sends messages back and forth and measures the average duration of those messages.

if finalDurationResult.avg > thresholdWithTolerance {

return fmt.Errorf("❌ average duration per executed event is greater than the threshold (with tolerance): %s > %s (threshold: %s, tolerance: %s)", finalDurationResult.avg, thresholdWithTolerance, config.AverageDurationThreshold, tolerance)

}

After making this change we actually saw this test start to fail periodically. I setup a background process to periodically measure top to see what might be causing this issue:

Process CPU/Memory (top 10 by CPU):

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

runner 17235 121 3.7 2941796 609660 ? Rl 21:20 3:55 /tmp/go-build2250316733/b1239/hatchet-loadtest.test -test.testlogfile=/tmp/go-build2250316733/b1239/testlog.txt -test.paniconexit0 -test.v=true -test.failfast=true -test.timeout=20m0s

You can see that we’re using a bit over 1 CPU in our test, this would intermittently cause the test to fail, complaining that things have gotten slower. Which highlights the major tradeoff with compression: You trade network bytes for CPU overhead.

Nothing in life is free; to compress you need to spend cycles on either end (the server and client) to actually calculate the sliding window + Huffman coding.

In our case, as the main modification was to reduce bytes transferred over the wire this is a efficient tradeoff, but that might not always be the case and its important to remember why you’re implementing compression in order to make that final decision.

Conclusion

To conclude, this was a extremely fun exercise in understanding the why and how of compression. Clearly there are serious benefits to compression your data over the wire, and in many cases if you can own both sides of the connection (e.g. the client and server), the benefits of increasing the CPU likely can outweigh the costs of network throughput.

And this serves as another reminder that the wizards of the internet have cooked once again. There are many things that we take for granted that allow us to build on top of, and its important to understand when and where to use these technologies.